The last posting on Lace triggered some interesting responses. Among them was the fact that a wedding dress was made of Nottingham Lace. Another reader wondered where one finds pieces of chunky old lace with which to play creatively. A third observed that the only place in the UK where lace continues to be manufactured is in Heanor in Derbyshire. And there was an email from Jeri Ames in Maine, USA with a request to share this blog with the members of Lace@Arachne.com.

That will be a pleasure and I hope that the lace makers will find this blog interesting though tangental. And for any readers with links to RSN in the 1950s, my name during my RSN days was Ann Nind. While a student there, I completed two and a half years of the three year course all in an 18 month time period. I worked hard for the first time on my life. It was a skill I really wanted to pursue but employment prospects were almost negligible. Hence the move into Occupational Therapy.

One never knows what will happen when one starts a blog. And it’s all rather exciting!

Lace is a huge subject and my blog barely scratches the surface. Further information on the history of Lace can be found in the article Lace by Sheila A. Mason, BA, FRSA. www.nottsheritagegateway.org.uk

Machine knitting was invented about 1589 by William Lee, a vicar of Nottinghamshire. The Stocking Knitting Frame made it possible for workers to produce knitted goods up to 100 times faster than by hand. The industry was primarily based in Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire and Derbyshire. The workers required quick sight, a ready hand and retentive faculties. It was a hard and demanding way to earn a living. Queen Elizabeth 1 refused to grant Lee a licence to produce stockings as she feared that it would result in financial hardship for the hand knitters. He went to France where he and his brother developed the machine further and within a decade he was able to produce long silk stockings for the gentry. Prior to this, stockings were hand knitted at home by every person available much like the production of Dorset Buttons.

www.frameworkknittersmuseum.org.uk

I am reminded of Malvolio in Twelfth Night written by Shakespeare 1601/02. By then, his yellow stockings had become a fashion item and it did not take long for them to become established. The cross gartering was not so normal! White was the usual colour and stockings were made of wool or cotton with silk being the most expensive. Fashion dictated colour changes and the inclusion of designs such as clocking as the machines became ever more complex.

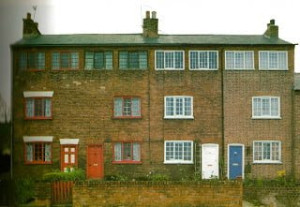

The hand operated stocking knitting frames were an integral part of a cottage industry in the homes and cottages of Nottingham. A good light was essential and the high set wide windows in the photograph below indicates that a knitting machine was installed in the upper rooms. It was a family occupation. The men operated the knitting machine, the women did the sewing up and the children wound the hanks of wool onto cones. The machines became better, larger and faster. The industry boomed. The hand operated Stocking Knitting Machine depicted below is very different to the complex machine being demonstrated in the video at the end of this entry,

These four cottages in Stapleford near Nottingham were purpose built for the home based stocking frame knitters. The large windows on the top floor let in as much daylight as possible. In 1844 there were 16,382 stocking frames in the area. But the home industry was in decline because the availability of steam power made it increasingly attractive for the industry to move into factories. As a result, many of the machines in the homes fell idle and the welfare of the workers deteriorated. To earn the same money, the worker now had to toil 16 hours a day whereas previously he worked 10 hours. Their living conditions became deplorable with a diet consisting mainly of bread, cheese, gruel and tea on which they grew emaciated, pale and thin. As you will see in the video, operating a machine by hand requires strength and coordination.

This photo and the information were found in a wonderful collection of pictures: English Cottages by Tony Evans and Candida Lycett Green, ISBN 0 297 78116 2.

As the 19th century progressed, fashions changed. Men wore trousers and no longer needed long stockings. In the years from the 16th century to the 19th century it became harder and harder to make a living from operating a knitting machine. This is a brief synopsis from a long and informative article at

www.picturethepast.org.uk

A Google search of Framework Knitting Machines will lead you to YouTube videos of these machines in operation. You will notice that working the 100 year old machine requires good body strength and concentration. The knitter, Martin Green, can be seen in the following video which includes an explanatory soundtrack.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oWfzzfjMa6k

The beautiful lace shawl pictured at the end of one of the videos reminded me that I have a similar shawl given to me by an English friend on the occasion of the birth of our first child. It is like gossamer and is in excellent condition because it has been treated as a treasure.

I hope that you have enjoyed this brief trip into the Land of Lace.